Church music. Is there any other aspect of our worship with so much power to lift us to the company of heaven, or plunge us into the depths of petty squabbling? We Christians are as passionate about music as we are about politics. Oh, the organist! Oh, the hymns! Oh, my tone-deaf neighbor!

I suspect that one reason for this passion is that we crave the blessings of good music: the experience of beauty, a sense of something greater than ourselves, a feeling of community, and the opportunity for praise. Our hunger is great, and we want worship to feed us with wonderful music every time we make the effort and get ourselves to church.

The problem, of course, is that a worship service is not just about being fed. We come to praise, to give thanks, to learn, and I would argue, to create an experience in which our neighbor can do the same. It’s not a show to watch. It’s not something the people “up front” do for us. When we join in prayers, when we sing the hymns–even the ones we don’t know or don’t like–we make worship happen. We do it for God and for ourselves and for others. And when we do it for others, our singing can be an act of hospitality.

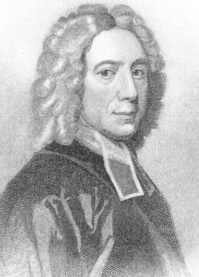

The Wesley brothers knew a thing or two about the power of hymns. You can find John Wesley’s “Directions for Singing” in the preface to the Methodist Hymnal. His instructions are plain, stern, and full of hope. He had such faith in what we could do if we sang with heart, soul, mind, and strength. It makes me smile. It makes me want to sing.

Directions for Singing

I. Learn these tunes before you learn any others; afterwards learn as many as you please.

II. Sing them exactly as they are printed here, without altering or mending them at all; and if you have learned to sing them otherwise, unlearn it as soon as you can.

III. Sing all. See that you join with the congregation as frequently as you can. Let not a single degree of weakness or weariness hinder you. If it is a cross to you, take it up, and you will find it a blessing.

IV. Sing lustily and with a good courage. Beware of singing as if you were half dead, or half asleep; but lift up your voice with strength. Be no more afraid of your voice now, nor more ashamed of its being heard, then when you sung the songs of Satan.

V. Sing modestly. Do not bawl, so as to be heard above or distinct from the rest of the congregation, that you may not destroy the harmony; but strive to unite your voices together, so as to make one clear melodious sound.

VI. Sing in time. Whatever time is sung be sure to keep with it. Do not run before nor stay behind it; but attend close to the leading voices, and move therewith as exactly as you can; and take care not to sing too slow. This drawling way naturally steals on all who are lazy; and it is high time to drive it out from us, and sing all our tunes just as quick as we did at first.

VII. Above all sing spiritually. Have an eye to God in every word you sing. Aim at pleasing him more than yourself, or any other creature. In order to do this attend strictly to the sense of what you sing, and see that your heart is not carried away with the sound, but offered to God continually; so shall your singing be such as the Lord will approve here, and reward you when he cometh in the clouds of heaven.

from John Wesley’s preface to Sacred Melody or a choice collection of psalm and hymn tunes, with a short introduction (1761)