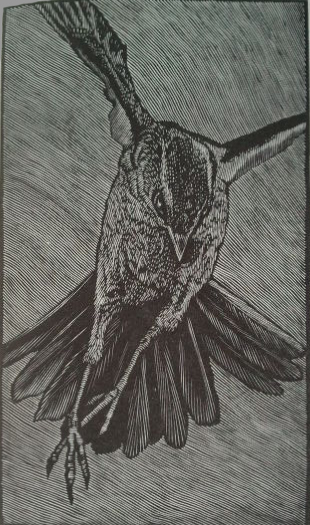

Earlier this year I was fortunate to be in Florence where I saw this relief of St. Luke the Evangelist by Lorenzo Ghiberti. In some ways, Ghiberti’s work is a traditional evangelist’s portrait showing one of the four evangelists writing and accompanied by the creature that is his symbol. Matthew’s symbol is an angel, Mark’s is a lion, John’s is an eagle, and Luke’s is an ox.

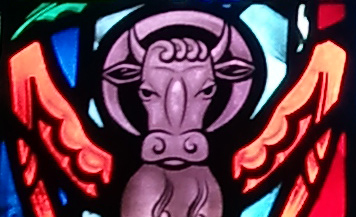

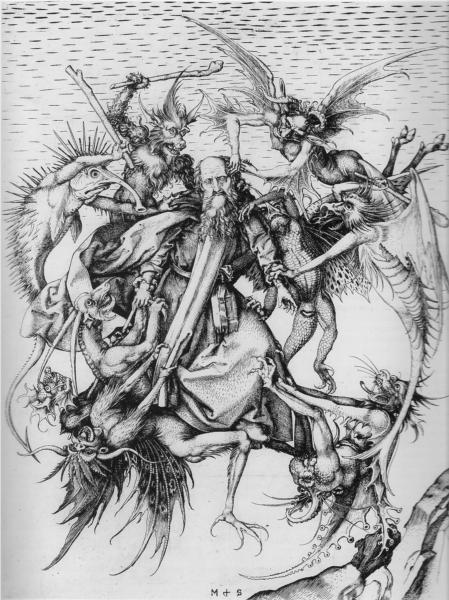

While I was thinking about Ghiberti and this relief, I realized what a challenge such a portrait of St. Luke could be. Lions, eagles, and angels are the stuff of visions, but a cow? Creating a dignified and powerful image of a man and a ox could be tricky–especially if you wanted to avoid anything reminiscent of Moloch or Mithras.

A quick survey of paintings and sculpture turned up a lot of interesting ways of depicting Luke’s symbol. Sometimes the ox or bull is clearly a spiritual being, as it is in the Russian icon below. At other times, as in the Netherlandish painting, the ox seems very much an animal, though one whose eyes suggest an otherworldly sentience.

St. Luke in the Hours of Mary of Burgundy, 1477

Photo: Wikipedia

In yet another example taken from a book of hours, the heavenly creature seems almost disguised as a earthly cow, calmly resting in the doorway while Luke paints a portrait of the Virgin Mary. It’s clear to me that, within this genre, the ox has presented artists with both a challenge and an opportunity for experimentation.

In the Baptistry door relief, Ghiberti appears to be trying something very different from other artists. There’s a connection between man and creature expressed through the composition. St. Luke’s right arm and leg line up with the the ox’s leg; their poses mimic one another.

In this way, Ghiberti’s ox is not just an identifying symbol or an animal sitting behind the writing desk. This ox interacts with the saint. The angles of Luke’s left hand and the scroll make a visual rhyme with the ox horns as it turns its head to look at the evangelist. The drapery and the chair legs repeat graceful shapes.

With so much gentle rhythm in its making, the composition is dancelike. There is movement within the confines of the quatrefoil, and there is unity of strength and grace, body and spirit. The ox is not massive and powerful, but surprisingly agile and elegant. Ghiberti’s animal is more than an attribute, he is a holy muse; a conduit for the inspiration of the Holy Spirit; a partner with the saint in the dance between God and man.